Dispelling the Mystery: Transparency and Unity in Course Module Design

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of blog posts about teaching online.

Tanya Long Bennett is a professor of English.

Although most of us have likely benefited from the self-reflection and slowed pace of life imposed upon us by COVID-19, we also grapple with high levels of frustration over the loss of valuable face-to-face time with our students. If we’re struggling, we should assume that our students are experiencing this stress as well. It may sometimes be tempting to consider them the source of our pain rather than partners in the work of higher education, but if we’re honest, we’ll acknowledge that students are too busy trying to keep their heads above water to sabotage our best laid plans on purpose. In fact, the real issue may be those plans themselves.

At institutions like UNG, most of us are proud of the emphasis on effective teaching; to our credit, UNG instructors tend to value our disciplinary expertise more as a resource for students than as a ticket to scholarly glory. I’ve observed colleagues who could walk into a classroom and, with very little attention to pedagogy, lure students into a whirlwind of intellectual exploration that left them enthralled with the subject matter—and with learning itself. Even so, the quick transition we made from in-class to online delivery in spring 2020 due to COVID-19 threw many of us into unfamiliar territory. In shock, we understood that the standards to which we held our students and ourselves would have to be relaxed a bit as we moved blindly forward. Most of us dealt sympathetically with our students, who had “not signed up for this,” and we simply did our best triage teaching to finish out the spring semester. But as we planned for a modified fall semester, we may have chafed at the realization that we would not be able to depend solely upon either our charisma or our disciplinary expertise to impact our students as desired.

Although college professors sometimes dismiss pedagogy as a tool primarily for K-12 teachers (a view perpetuated by the fact that most graduate schools require little-to-no pedagogical training before assigning TAs to teach core-level classes), I propose that we reconsider this attitude and learn from our public school colleagues in order to ensure our students’ success this year, and perhaps even beyond.

In this blog essay, I’d like to propose a simple strategy that offers improved transparency to communications about weekly assignments that can otherwise be opaque. In response to a summer 2020 conversation between me and my husband, Chuck, who is assistant principal at a local middle school, I gave my own D2L English Composition II course a closer look. He was working hard with his administrative team and the teachers in his school to develop a template for daily virtual lessons that would enable parents and children to navigate their assignments successfully across multiple courses. He noted that, because teachers had all developed (in the urgency of the spring transition) their own ways of mobilizing the tools of the online platform, no two courses looked alike. Even figuring out which tool a teacher was employing as his/her central information hub was a challenge. Chuck argued that not only was the stress of this hyper-navigation unnecessary, it also signaled a missed opportunity. A good lesson, he asserted, is tightly unified, and the appearance and organization of a course and its lessons on an online platform should be elements of unified course design.

Here, I must stop and give a much-deserved shout-out to UNG’s DETI staff: For years, they have insisted on, and offered support for, unified course design. In one of the many help sessions Jeannette Mann offered me during my early struggles with D2L, she finally conquered my stubborn habit of plopping a linear syllabus into D2L and simply expecting students to “follow it” as they did in a face-to-face class. She led me like the blind Saul to a conversion moment when the scales fell off my eyes, and I mumbled, in my ecstasy, “Oh, I see! It’s a web.”

The simple strategy I offer here just expands on a concept that DETI has been promoting for years: an easily navigated course module strategically aligned with course learning outcomes. To the basic concept, I have added three elements that I believe improve students’ ability to complete weekly assignments, recognize the goals of those assignments, and manage their time:

- An introductory pre-lesson overview,

- Estimates of how long each task will take, and

- A task-completion checklist.

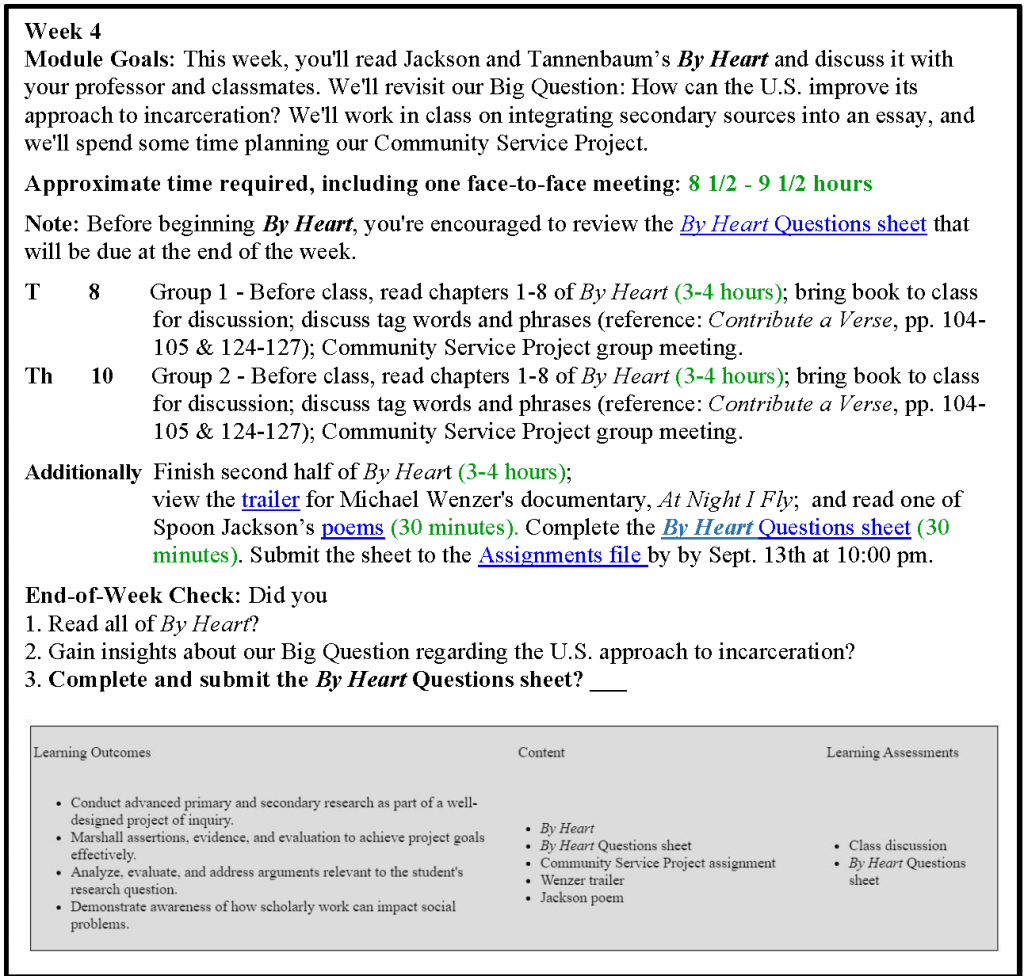

Here’s an example of a module that utilizes these elements:

Note that the Module Goals in the example above do not include course learning outcomes. Those are referenced at the bottom of the module instead, since students beginning a module are most interested in knowing what needs to be completed this week. This pre-lesson overview, Module Goals, is meant to prime students cognitively, to prepare them for the general work we are embarking upon for this “chunk” of time. The Learning Outcomes chart at the end of the module is available for students wishing to consider how the lessons are meant to promote overarching learning goals. But as we all know from experience, readers seeking the “meat” of an information source often skip over text that is not immediately pertinent. To address this problem, I usually begin courses with a review of the course learning outcomes and then assign a reflective essay at the end of the semester requiring students to discuss their progress toward those outcomes, linking that progress (or lack thereof) to specific course assignments and activities. Of course, I weave the language of the outcomes throughout course materials as well. But I made the decision to move the chart to the bottom of the module this fall, reasoning that if students’ eyes are skimming past the chart for “meat,” they are more likely to miss crucial information needed to complete the week’s tasks.

In light of this pre-lesson overview and the weekly assignments laid out (and hyperlinked) in the schedule, it might seem like overkill to close the lesson with the End-of-Week Check, but as I assert with first-year composition students who detest writing essay conclusions, “Would a lawyer give up her chance to deliver closing arguments to a jury?” This checklist catalyzes a review of the module and an inventory of what should have been completed and submitted that week. It serves as a vehicle for cognitive reflection and provides closure to the individual module.

Once, before my conversion, I complained to Jeannette, “The information is here in the syllabus. I don’t see why I need to repeat it twenty times for students to get it.” She smiled patiently and answered, “No, don’t you see? Redundancy is built into the course design. Everything is linked. The student should be able to get to the information through a number of different paths.” Students can read the syllabus I’ve posted in the “Begin Here” content file and link to materials and tasks from the full-semester schedule provided there. But the “chunked” course modules are a much more effective tool for helping students manage their work and time. Further, my new course module template has yielded some surprising insights for me, the instructor. As I began estimating how long each activity in a module would take, I began seeing problems with the timeline I had set up. I might have surmised that students would have “plenty of time” to draft a five-page essay over a three week period, but I had, in some cases, assigned fifteen hours of work in one week and four in another. Detailing time requirements in the modules not only helps students follow my directions, but it has also led to my revising my course plan in some cases.

This proposed modification for course modules is only one example of the ways that our communication with students can be improved to boost student learning in an online environment. We may be tempted to let ourselves off the hook regarding course quality during these strange times, but if we’re willing to consider new strategies, we may stumble into pedagogical discoveries that impact higher education beyond our current restricted situation. We may discover, once this virus is under control, that some of the practices we’ve developed are worth keeping. Perhaps the online teaching experience, wanted or not, has the potential to make us better teachers.

Leave a Reply